ARTIST BIO

Edward Beckett,

a symbolic expressionist,paints the unseen; he paints emotions and aspirations, giving form to these and the intertwined relationships of human existence. The artist has created a somewhat standardized and recognizable visual vocabulary to communicate the very real interconnectedness of living.

Edward Beckett,

a symbolic expressionist,paints the unseen; he paints emotions and aspirations, giving form to these and the intertwined relationships of human existence. The artist has created a somewhat standardized and recognizable visual vocabulary to communicate the very real interconnectedness of living.

Beckett's mediums include printmaking, acrylic painting, iconography, and ceramics. Born in Huntington, West Virginia, he studied with June Kilgore at Marshall University in West Virginia. He then went on to complete his undergraduate work at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York.

Edward Beckett's art has been showcased in solo exhibition on both West and East (North American) coasts as well as at The Works--a major summer art festival in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, where he was honored as a Guest Artist. The recipient of many awards, his work has been cited by art critic Peter Frank, and Frank Gettings, curator of prints at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC, among others.

Gordon Fuglie, Director, Laband Art Gallery, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, points out that, "Beckett attempts in his paints and prints a reinvigoration of the 'marvelous', a notion that gave a charge to the early images of the Surrealists. He differs from them, however, in that rather than creating a new reality, he reckons directly with his time and place through symbols that embody the myriad possibilities and perplexities of communication."

SUBJECT-MATTER ADDRESSED BY THE ARTIST

Questioning Time: A Question of Time

All of my artistic explorations have involved the representation of the unseen-but felt-influences in our daily lives. The process of delving into the depiction of unseen communication has led me to the discovery of time as a subject.

All of my artistic explorations have involved the representation of the unseen-but felt-influences in our daily lives. The process of delving into the depiction of unseen communication has led me to the discovery of time as a subject.

Time is the omnipresent sea that we all swim through every day of our lives. It is a fascinating subject because it never stops.

"Every second from birth is spent experiencing; different sensations, different interjections, different directional vectors of force/energy constantly compose and recompose themselves around you. Time (situations in a visible logical progression) never will and never can repeat itself."

This statement by artist Keith Haring, tries to explain the ephemeral quality of time. There is never a pause to study, feel, taste or visually notate time.

My work is only the beginning of a challenging quest to capture the visual representation of time's influences on our lives, our decisions and our ultimate passing.

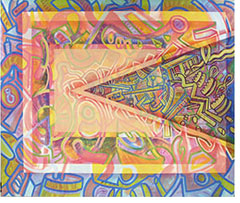

Visual Song: Welcome to the World of Visible Sound

Having worked the last several years on the depiction of time and other invisible forcesthat wind their way around and through us and that are indeed affecting our lives, it was a natural extension to begin the process of showing the invisible world of sound-musical sound to be exact- coming at us from a myriad of sources.

Having worked the last several years on the depiction of time and other invisible forcesthat wind their way around and through us and that are indeed affecting our lives, it was a natural extension to begin the process of showing the invisible world of sound-musical sound to be exact- coming at us from a myriad of sources.

When possible, I have created these images in the presence of the composer, performer(s) or orchestra performing in a live setting. The sound waves of the melodie and refrains wash over me and visual images develop in my mind. The sketchbook that is ever-present in my hands, then receives the images.

This automatic drawing or auto automatism, espoused by the Surrealist artists and adopted by some of the Abstract Expressionists like Pollock and Motherwell, is the basis for all of the images in this show. In a few instances, the images were created while listening to recordings, but most of the art in this show was begun as propecia generico or as harmonic vibrations from live musicians. Many of the musicians have been kind enough to autograph the sketches created through the influence of their creative performances.

I feel that it is important to show the ink drawing from which the pieces were developed. The connection to the raw line is important to understanding the energy that went directly to the paper and is in turn connected directly to the work of art.

Music is diverse in its style and content. Different methods have been used to depict the variety of musical styles but the connective iconography of forms and feelings are a continuous thread that weaves through the whole body of work.

Some music produces images of volume, harmony and drama while others find themselves showing a narrative of forms. I don't edit what my mind's eye sees. The varieties of music experiences have all produced their own unfolding story. You will find secular and sacred reactions in this show; spirituality and message abound in these pieces.

When I look at the art, I can still hear the music. I encourage my viewers to listen as well; listen to what you hear and pay attention to what you feel. I hope that the music in the art will speak to you on some level and excite your visual hearing to blossom into an image of sound.

You may be familiar with the piece or pieces that are the root impression for these works; in that case you will have an even richer experience and possibly a revelatory one at that. Listen to the colors, meditate on the line and allow yourself to feel the Visual Song.

Of Self: Exploring the Unseen

My artwork is about painting the unseen elements of communication. These elements include communication (spoken, unspoken and musical) between ourselves and another person, our community, our world, our fears, loves and ambitions and between our perceptions of ourselves and all influencing factors.

My artwork is about painting the unseen elements of communication. These elements include communication (spoken, unspoken and musical) between ourselves and another person, our community, our world, our fears, loves and ambitions and between our perceptions of ourselves and all influencing factors.

I am irresistibly drawn to discovering and rendering all forms of communication. If we can behold (unseen) communication, perhaps we can appreciate it more; if we can appreciate it more, perhaps we can improve the world in which we live.

Icons From Antiquity and Into the Future

Edward Beckett's new variation on an ancient art form, the Secular Icon, begins with Sacred Iconography. Icons are an art form that began in the 3rd Century and are governed by rigid cannons and principles.

Edward Beckett's new variation on an ancient art form, the Secular Icon, begins with Sacred Iconography. Icons are an art form that began in the 3rd Century and are governed by rigid cannons and principles.

Beckett's art form is infused with the artist's expressionist approach. Beckett explains, "In theologically correct Icons, the connection with the universe and divinity is pretty narrow. Meaning, to understand and appreciate the theologically correct use, one needs to be an Orthodox Christian, Roman Catholic, Episcopalian, etc.

I feel that the experience of spiritual connection or contemplation--of any type--should be extended to everyone. The Secular Icon is not just the juxtaposition of two different thoughts or images but a true combination of ancient Iconography and Symbolic Expressionism. The Secular Icon embodies the tweaking of an ancient theme."

ESSAYS

September 2006--Edward Beckett: Musical Ekphrast

By Peter Frank

Los Angeles

Artists and musicians have struggled to meet and match one another's art forms ever since - well, ever since there was art and music. Some creative individuals have built upon their synesthesia, creating forms and colors from sounds and timbres or vice versa because their "miswired" senses tell them to. Others practice more than one art form, seeking equal levels of - but not necessarily equivalent - expression in disparate disciplines. Still others seek somehow to meld the two disciplines, to fuse the two apparently antithetical modalities into Gesamtkunstwerk, "total works of art" that might also include dance, theater, poetry, and/or other art forms. And then there are those who engage in a form of sonic-visual ekphrasis. These artists and musicians seek consciously to mirror the experience, and in many cases the perceived contents, in their native medium of specific works in the other medium. Quite evidently, Edward Beckett is a dedicated ekphrast.

The term "Ekphrasis" began life long before we did, as a term in ancient Greece pertaining to rhetoric. As defined in Wikipedia, "Ecphrasis[sic] has been considered generally to be a rhetorical device in which one art tries to relate to another art by defining and describing the essence and form of that original art, and in doing so, 'speak to you' through its illuminative liveliness." Although originally, and still prinicipally considered, a literary phenomenon, in which primarily descriptive art forms recapitulate what is seen in primarily visual forms, ekphrasis is now regarded as a universally reflexive condition available to all artistic disciplines, so that, as Wikipedia continues, "a painting may re-present a sculpture, and vice versa; a poem portray a picture; a sculpture depict a heroine of a novel; in fact, given the right circumstances, any art may describe any other art, especially if a rhetorical element, standing for the sentiments of the artist when he created his work, is present."

Given its essential abstractness, music evaded the discourse of ekphrasis until composers became routinely engaged with extra-musical qualities - that is, with strategies of sonic depiction, making pictures and telling stories in pure sound (as opposed to accompanied word) - in the 19th century. An extra-sonic teleology motivates the tone poem, the aural landscape, and even the "song without words," bringing music into the realm of the "seen." The 20th century furthered the availability of music to its sister arts, thanks to efforts of both musicians and other artists to emulate conditions otherwise unique to the opposing forms - and thanks also to the emergence of new art forms such as film that more nearly manifest the Gesamtkunstwerk.

"All the arts," opined Walter Pater toward the end of the 19th century, "aspire to the condition of music" - that is, to the condition of abstraction. It is ironic that this aspiration to mediumistic self-sufficiency was induced and finally realized by the interfunctioning of the various art forms - that Vasily Kandinsky, for instance, could "invent" non-objective painting by emulating music. Edward Beckett's aspirations to music come a hundred years after Kandinsky's, and clearly benefit from the Russian-German painter's breakthroughs. But they benefit even more from what we most readily think of as music's own side of the ekphrastic equation: the aural depiction of visual phenomena. Beckett very specifically and very consciously reverses this formula, effecting the visual depiction of aural phenomena. Many other painters have done so, including Kandinsky himself, his friend Paul Klee (who was also an accomplished violinist), František Kupka, the painter-animator Oskar Fischinger, and so forth. We note their oeuvres overall for their dedication to a visualized music. But for individual works creating an ekphrastic bridge between music and painting, we remember soonest the composers who have sonically re-pictured artworks - Mussorgsky with Pictures at an Exhibition, Rachmaninoff with Isle of the Dead, Hindemith in Mathis der Maler, right down to Gunther Schuller's Seven Studies on Themes by Paul Klee and Anthony Turnage's Three Screaming Popes and other homages to Francis Bacon.

The ambitiousness and intricacy of Beckett's painterly - and draughtsmanly - responses to music betrays the hope that out of this continuing effort can come something signal, monumental, equal to the work it reconfigures. Kupka and Kandinsky produced that kind of masterwork, as did Fischinger on film, but in giving visual form to the well-known compositions of artists long established, and long dead, when they essayed their equivalents, the early 20th century European artists put themselves at a distinct disadvantage. Kupka, spectacular painter though he may be, will always look like Bach, while Bach will never sound like Kupka. Kandinsky's ekphrastic reflections on the work of Arnold Schoenberg, oblique and one-time though they may be, put the painter in direct response to the work of a contemporary, and the works produced maintain a stature similar to those they embody. In this regard Beckett is wise to respond with the greatest ekphrastic precision to the musicians, classical and popular, of his own time. His effulgent responses to music as diverse as the jazz-inspired work of Edward Cansino and recent orchestral music of John Adams brims with immediacy, and the mural-size painting derived from From Me Flows What You Call Time by Toru Takemitsu matches the late Japanese composer's universe of sonic impressions in its luscious detail and its enveloping breadth.

If these responses to contemporary music come close to matching their mirrored subjects in prominence as well as ambition, Beckett's ekphrastic rephrasing of Ravel's Bolero and American "roots" music is no less finely wrought or deeply felt. It consists of the same vocabulary of forms, Beckett's distinctive "constructive whirlwind" of shapes described by line and seemingly injected with color - a basically playful style that is nevertheless impelled with a gripping urgency, an urgency we feel as an almost choreographic response to "organized sound" (as Edgard Varèse described music). There are many senses of motion at play in Beckett's art, flow and bounce, cyclone and arc, walk and fly; wisely, Beckett does not employ these as a kind of systematic equivalent to the tempi in the music he responds to, but as an embodiment of his own visceral response to that music - the tempi inside him, which could be agitated by a very un-agitated passage coming out of someone's saxophone, or becalmed by a rush of orchestral harmonies.

Beckett exploits the fact that ekphrasis is an inexact process; like any serious ekphrast, he recognizes inherently that an ekphrastic artwork is not a mere portrait of the work on which it is based, but a point of departure and of return, a catalyst for re-invention, not just for reflection. He never flies far from the music in question, but the music in question flies far itself, allowing for rhapsodic but not for inappropriate liberties with the sense of the music. No code of equivalency (red = E-flat, for instance, or trumpet, or fast march speed) binds Beckett to a superstructure that forces him to think of his paintings and drawings as visual "performances" of the work. Rather, his artworks function as diaristic jottings, neither performance from a score nor bringing forth of embedded subject matter but notations of listener response.

If Beckett's musically impelled artworks emerge at that distance from the musical material, are they still truly ekphrastic? Do they reflect the music, or do they reflect Beckett's response to the music? Both. Their basic imagery has little if anything to do with the music at hand; it has to do with Beckett's own style, cultivated over a substantial career. There are musical associations, such as abstracted instruments, ecclesiastical tropes, and the hint of figures performing - and combinations of all these and more. These all operate in the service of the music - and equally in the service of how Beckett feels about that music. That would seem obvious - Beckett's response to the ekphrastic subject would seem central to the process - but it can't seem too clear. Yet there are these clear images, "feeling" like the music they embody. They do not accompany sounds, they convert them into metaphors of sensation. But those metaphors of sensation derive directly and solely from the Blues pieces or symphonic passages Beckett has heard in concert or on the radio or in recording, musical works to which he has gravitated or finds himself delightedly beholding. Ekphrasis is necessarily an indirect relationship when it bridges the very different realms of sound and image; a lot of feeling can pass under that bridge, and Edward Beckett lets it flow into his art.

October 1999--Edward Beckett: Meanings and Mechanisms

By Peter Frank

Los Angeles

The cartoon spirit animates (as it were) the mediumistically varied but stylistically cohesive work of Edward Beckett. But if Beckett festoons his paintings, prints and pottery with unlikely machines, starkly described, curiously anthropomorphic, and propelled into a perpetual motion of apparently antic energy, he does not do so merely to provide the fine-art equivalent of Saturday-morning kids' television. Neither, of course, did Roy Lichtenstein or Keith Haring, artists (also in a variety of media) synonymous with a cartoon aesthetic. Like theirs, Beckett's less evidently and less directly narrative art conveys concepts, sensations and responses to a world of inner passions and outer pathos, of human history and the responses of a single soul to that history's tragedies and triumphs.

It would be presumptuous of this writer, however well informed, to describe (much less analyze) the iconography of Beckett's imagery. That which Beckett wants to convey, he -- certainly through his art -- can best delineate. (He refers to the possible content of his work in deliberately oblique terms, describing them only as "the unseen but felt powers and influences" that "shape us and elude us".) Indeed, as in any essentially abstract mode, the sources of the images are arguably secondary to the sensation(s) conveyed by those images; the encoding of meaning here serves to communicate the envelope of that meaning rather than its mere account, rather like the musical setting of a poem couched in obscure language.

Suffice it to acknowledge that Beckett responds fervently, sensitively, and with abiding hope and faith to the often-disturbing headlines of our era and our century. His vivacious forms, his similarly vivid employment of color, and the eccentric conformations on which he is wont to rely (especially but not exclusively in clay) all bespeak an optimistic outlook on life. But from their intricacies, their un-mechanistic (indeed humanoid) contours, and the intensity of their rendering, a viewer can readily tell that those forms are as capable of anguish and tragedy as they are of wit and exuberance. Although they mimic functional mechanisms (often seeming to be mechanisms at the point of malfunction), Beckett's images are not merely robotic, but metaphoric in their curious and delightful sinew.

Again, what concerns us here is not what is being metaphorized, but how Beckett's images metaphorize -- not meaning, but the mechanism of meaning. Quite obviously, it is the working of mechanisms that is itself the overriding metaphor; if we are to see ourselves in these devices, how they operate is how (Beckett says) we operate. In this light, it is remarkable that the artist does not insist, as is the fashion, that we are, one and all, headed for a breakdown. Beckett's effervescent style underscores his evident belief that we may be due for a tune-up, even overhaul; but we are not clanking and whirring our way to oblivion. If entropy is inevitable, Beckett's eccentric but persistent contraptions aver, it is not imminent. Humanity has not yet reached the lip of its own obsolescence.

So what are Edward Beckett's images, and how are they saying all these reassuring things about us? They do so by exploiting some of the most eye-catching materials available to artists, as well as by engaging Beckett's own skill, cleverness, and innate verve. His woodblock prints, monotypes, low- and high-fire ceramics, and acrylic paintings normally muster the across-the-room impact of a circus poster. Certain of his designs would make ideal screen-savers, their pipes and gears, sprockets and sunbursts glowing and convulsing with a rough-hewn expansiveness mercifully free of most screen-savers' glib, over-compliant slickness. In fact, cinematic animation would seem the logical medium for Beckett to explore next.

Animation would seem a natural realm for Beckett not only because his images share a common stylistic language -- comically conceived, simply and forthrightly drawn -- with filmic cartooning, but because a preoccupation with time itself underlies his work. Beckett considers his art "...the beginning of a challenging quest to capture the visual representation of time's influences on our lives, our decisions and our ultimate passing." If he encourages any specific interpretation of his loopy, tendrilous machines and spectral humanoid figures, Beckett directs us to the consideration of temporality, even describing his images, at least by inference, as "the ropes and worms of time," or enmeshed in as much. In their apparently repetitive but eccentric motions -- and in the entropy that seems to be creeping over them -- Beckett's clanking characters, be they creatures or contraptions, live in time every bit as much as we do. This despite their imposing bulk or power -- which, in Beckett's view, is an ironic monumentality, an Ozymandian pretense that proves no match for the forces of decay.

There, you see? No sooner does this writer declare it presumptuous to interpret Beckett's iconography, but he reads vast narrative concepts and moral precepts into it. Despite his own caveats, the artist's temporal allusions and fanciful imagery make it hard to ignore their content -- or at least to ignore the fact that they are content-laden. We are hard-pressed to comprehend Beckett's work as eyewash, no matter how sweet his colors, no matter how clownish his forms; the ambition clearly invested into his personages and contraptions insists we take them seriously, compassionately, even empathetically. Edward Beckett's abstraction finally pays homage to the modernist tradition not just by eliding prosaic equivalents, but by encouraging the apprehension of poetic ones.

Interpretation is as irresistible as it is incompletable. With Beckett, the volatility of mechanism and of meaning leads to stability in the mechanism of meaning -- a stability that not only allows, but requires you, the viewers, to be crucial cogs in that machine.

-----

Peter Frank is art critic for the L.A.Weekly, contributor to many art and general publications, author of several books, and organizer of numerous museum and gallery exhibitions in America and abroad.

August 1997--Critical Commentary on Edward Beckett

By Gordon Fuglie

Director, Laband Art Gallery, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles

With acrylic paints, ceramic sculpture and printmaking media, Edward Beckett produces images that examine the range of human communications from the electronic media to the interpersonal, and with the divine. As such, his paintings and prints are simultaneously somber and playful, surreal tableaux that uncannily incorporate large areas of decorative pattern around his humanoids, machines and framing devices. Beckett's work seems to refer initially to the cacophony of electronic sound and projected imagery that has swamped so much of our public and private spaces, but they also serve as metaphors for interior aspiration and compassionate action. In these perceptions, his zig-zags, diagonals, saw-teeth and jagged ovoid bursts externally the equivalent of the sonic bombardment of our consumer culture are Beckett's personal signs for his spiritual and socio-political concerns that he places within his intense compositions.

In his desire to discover and define the plethora of communications and transmissions of our age, Beckett will employ frequently as a motif a quirky mechanized being composed of connectors, wires and transistor-shapes. These forms are perhaps realized best in his color woodcuts where strong linear and chromatic contrasts give them a darkly radiant mysterious presence.

Beckett attempts in his paintings and prints a re-invigoration of the "marvelous", a notion that gave a charge to the early images of the Surrealists. He differs from them, however, in that rather than creating a "new" (sur)reality, he reckons directly with his time and place through symbols that embody the myriad possibilities and perplexities of communication.

|

|

My artwork is about painting the unseen elements of communication. These elements include communication (spoken, unspoken and musical) between ourselves and another person, our community, our world, our fears, loves and ambitions and between our perceptions of ourselves and all influencing factors.

I am irresistibly drawn to discovering and rendering all forms of communication. If we can behold (unseen) communication, perhaps we can improve it or appreciate it more.

I capture these mercurial, ephemeral and/or percussive interchanges "seen, unseen and felt" and shape them into revealing visual snapshots.

-Edward Beckett

VIDEOS

Click above to view

"Visual Song" Exhibit

Video with Music

SUBJECT-MATTER ADDRESSED

BY THE ARTIST

Questioning Time: A Question of Time

Visual Song: Welcome to the World of Visible Sound

Of Self: Exploring the Unseen

Icons From Antiquity and Into the Future

ESSAYS

September 2006--Edward Beckett: Musical Ekphrast

By Peter Frank, Los Angeles

October 1999--Edward Beckett: �Meanings & Mechanisms

By Peter Frank, Los Angeles

August 1997--Critical Commentary on Edward Beckett

By Gordon Fuglie, Director, Laband Art Gallery, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles

|